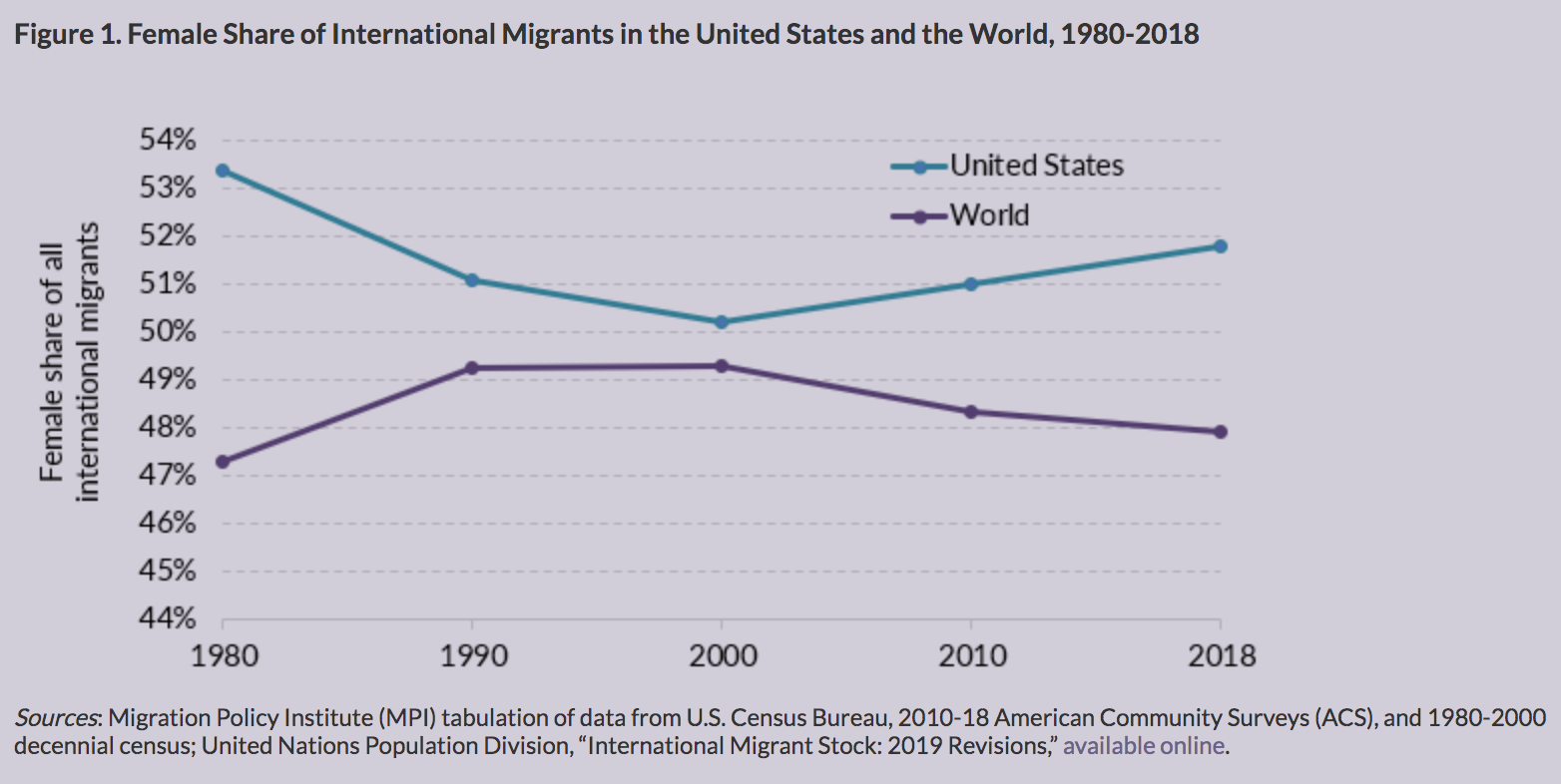

Women and girls made up slightly more than half of the 44.7 million immigrants residing in the United States in 2018. The female share of the foreign-born population is higher in the United States (52 percent) than it is globally, where women and girls account for about 48 percent of all international migrants (see Figure 1). One explanation for this difference is that close to two-thirds of the global migrant population is made up of migrant workers, who are more likely to be male (58 percent of all international migrant workers) and who often are not allowed to bring families along. In contrast, family reunification dominates U.S. immigration flows.

Immigrants represent about 14 percent of all females residents in the United States. As mothers, workers, and students, female immigrants make important contributions to local communities, the economy, and society. They come from diverse origins and linguistic backgrounds and have varying levels of education and work experiences, which in turn shape their social and economic integration. Their experiences in the United States compared to immigrant men and to U.S.-born women raise implications for sending and receiving countries, with respect to labor opportunities, family structure, gender roles, and more.

Using data from the United Nations Population Division, the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey (ACS), and the Department of Homeland Security’s Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, this Spotlight provides information on the population of female immigrants in the United States, highlighting their education, employment, marital status, fertility, and other key socioeconomic characteristics, with comparison to both native-born females and immigrant men.

Note: Unless stated otherwise, this Spotlight uses “female” and “women” interchangeably given that most female immigrants are adults.

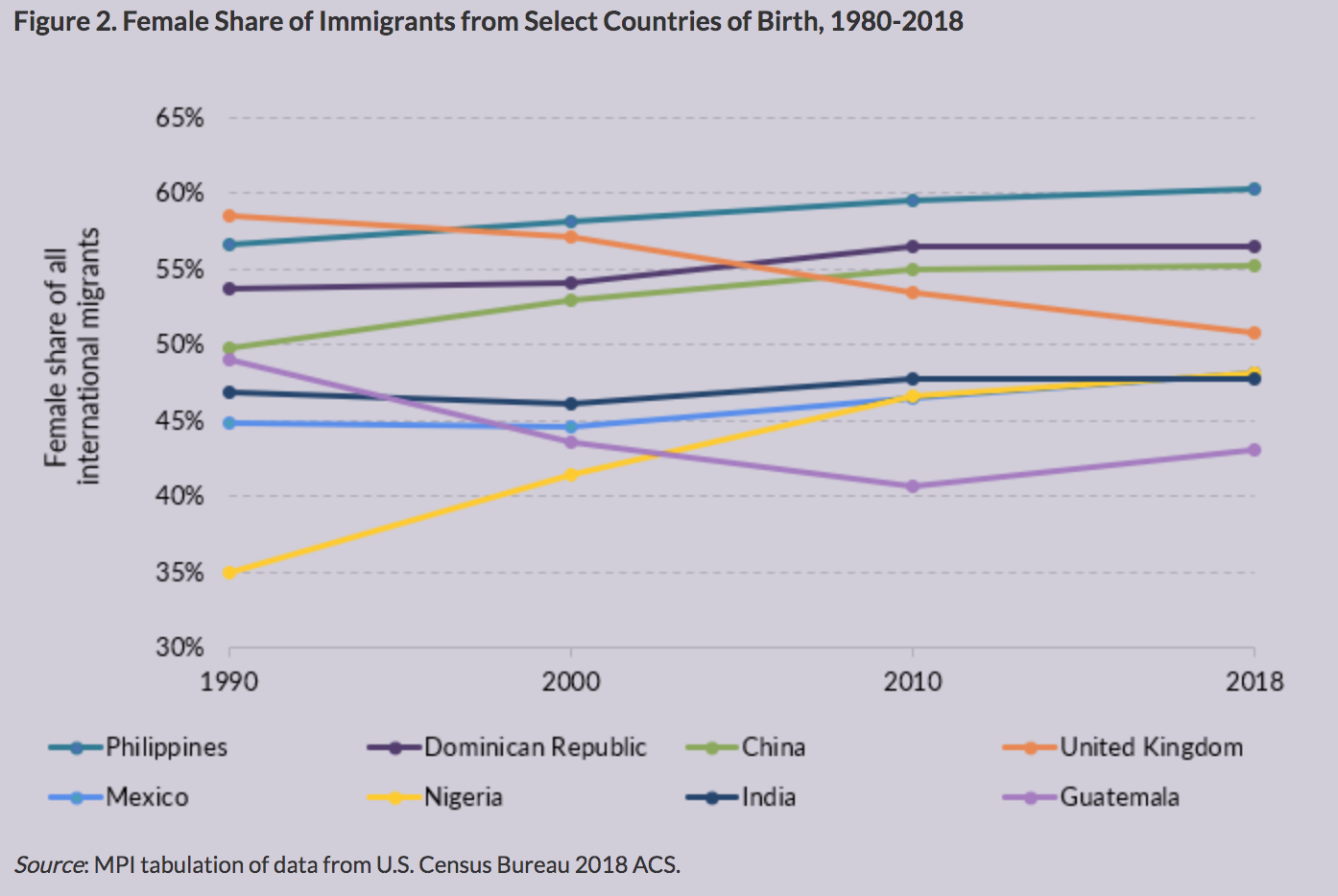

Origins. The gender composition of immigrants varies greatly by country of origin and over time. Overall, immigrants from the Caribbean, South America, Asia, and Europe are more likely to be women, while those from Mexico and Central America are more likely to be men. The patterns reflect the changing gender make-up of new arrivals, longer longevity of women, and the main pathways and reasons individual origin groups come to the United States, following the last major revisions to the U.S. immigration system in 1990.

As of 2018, 60 percent of immigrants from the Philippines were female, and their share has grown over time, driven in part by family reunification. Immigrant flows from the Dominican Republic have historically been female dominated, whereas the opposite was the case for immigrants from Mexico. The female share among Dominican immigrants has been consistently at least 7 percentage points higher than among the Mexican born since 1980, although both have experienced increases over the last three decades. Among other interesting trends: The female share among Nigerian immigrants grew from 35 percent in 1990 to 48 percent in 2018, while women represent smaller shares of immigrants from the United Kingdom and Guatemala today than they did in 1990.

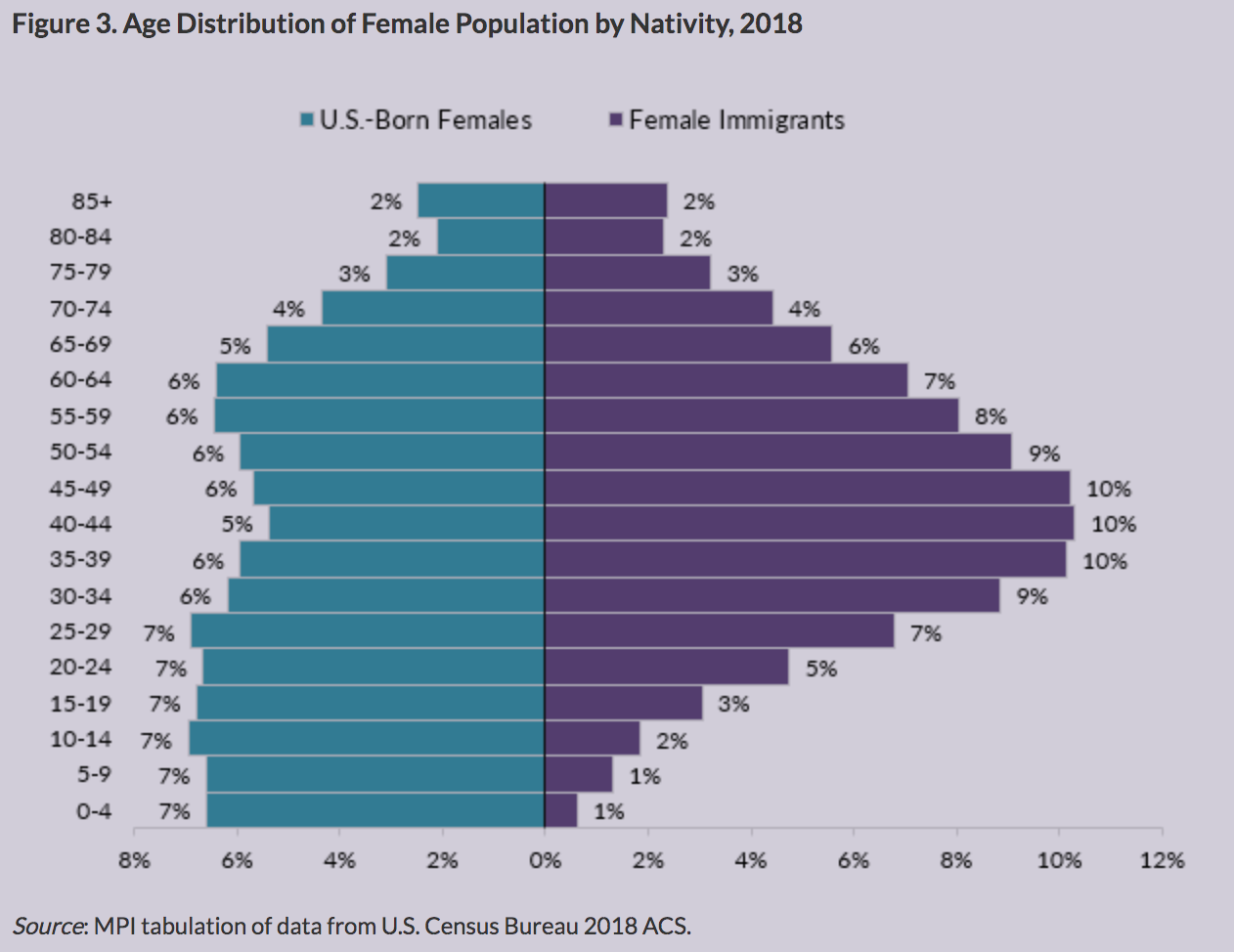

Age and Marital Status. Immigrant women were generally older than U.S.-born women, with average ages of 47 and 39, respectively, according to 2018 ACS estimates, which has a lot to do with the different age distribution among the foreign- and native-born female populations (see Figure 3). Immigrant women are significantly more likely to be of working age than their native-born counterparts because immigrants tend to come to the United States for work and family reunification. Children born in the United States to immigrant women are U.S. born, further skewing the U.S.-born population’s age distribution to younger age groups. Twenty-seven percent of U.S.-born females are under age 20, compared to only 7 percent among female immigrants.

Immigrant women are also slightly older than immigrant men, whose average age was 45 (compared to 37 for native-born men). Although immigrants overall are more likely to be of working age (18 to 64) than their U.S.-born counterparts, immigrant men were slightly more likely to be in this age range than immigrant women in 2018: 80 percent versus 77 percent.

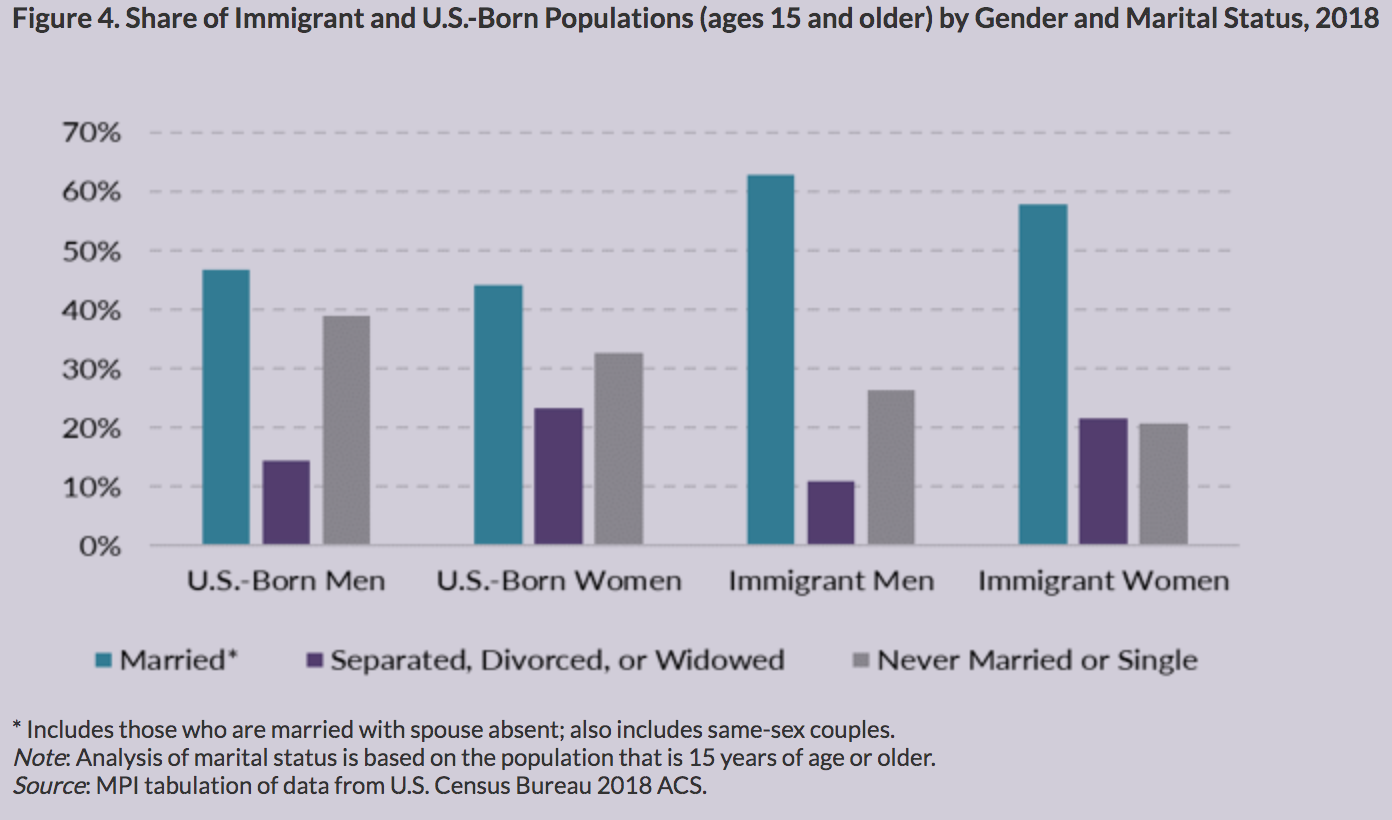

As a whole, immigrants are more likely to be married, and less likely to be separated, divorced, widowed, or single than the native born, regardless of gender (see Figure 4). Men, regardless of nativity, are more likely to be married as well as single, but are less likely to be separated, divorced, or widowed compared to their female counterparts. Immigrant women were much more likely to be married in 2018 than U.S.-born women: 58 percent versus 44 percent.

Fertility. Immigrant women ages 15 to 50 were slightly more likely to have given birth in the last 12 months (6 percent) than U.S.-born women in the same age group (5 percent), according to estimates from the 2018 ACS. Among those who gave birth, immigrant women were more likely to be married than native-born women (78 percent versus 63 percent).

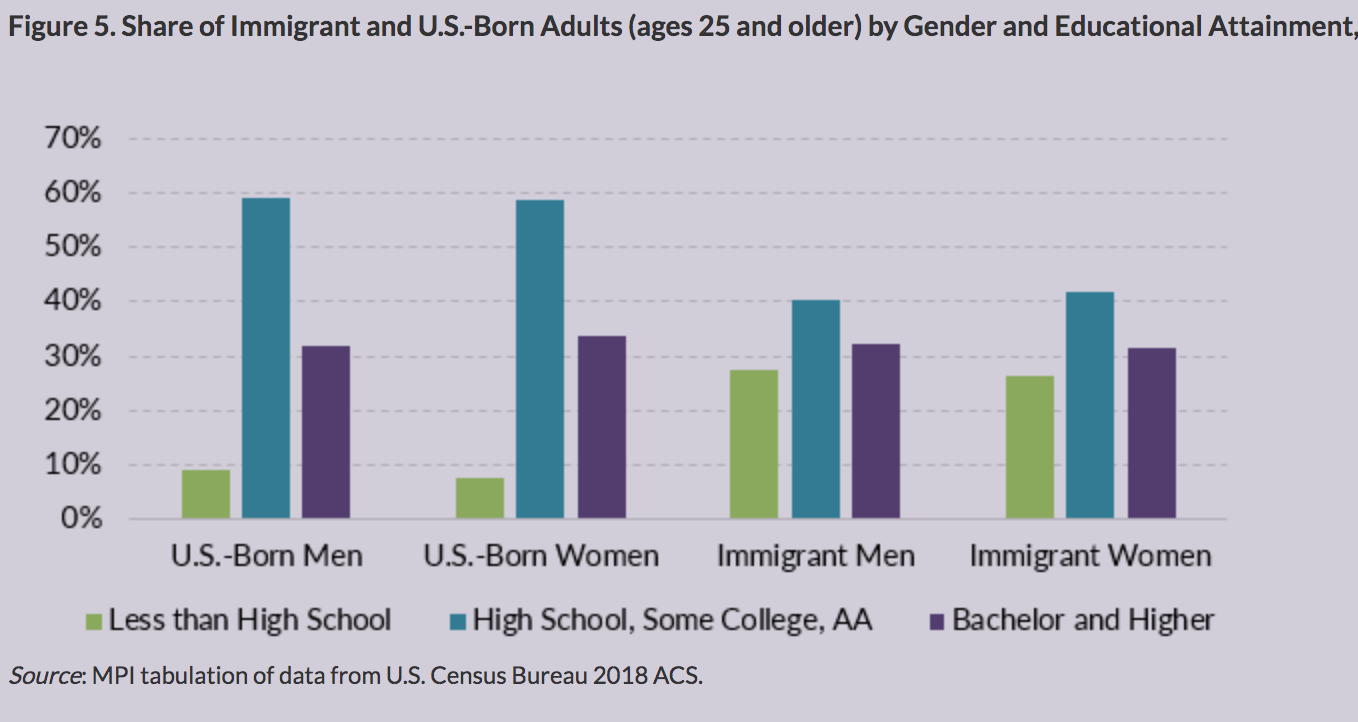

Educational Attaintment. While immigrants are more likely than their native-born peers to lack a high school education and as likely to have a four-year college degree, there was little variation in the educational attainment between women and men among all immigrants and natives in 2018 (see Figure 5).

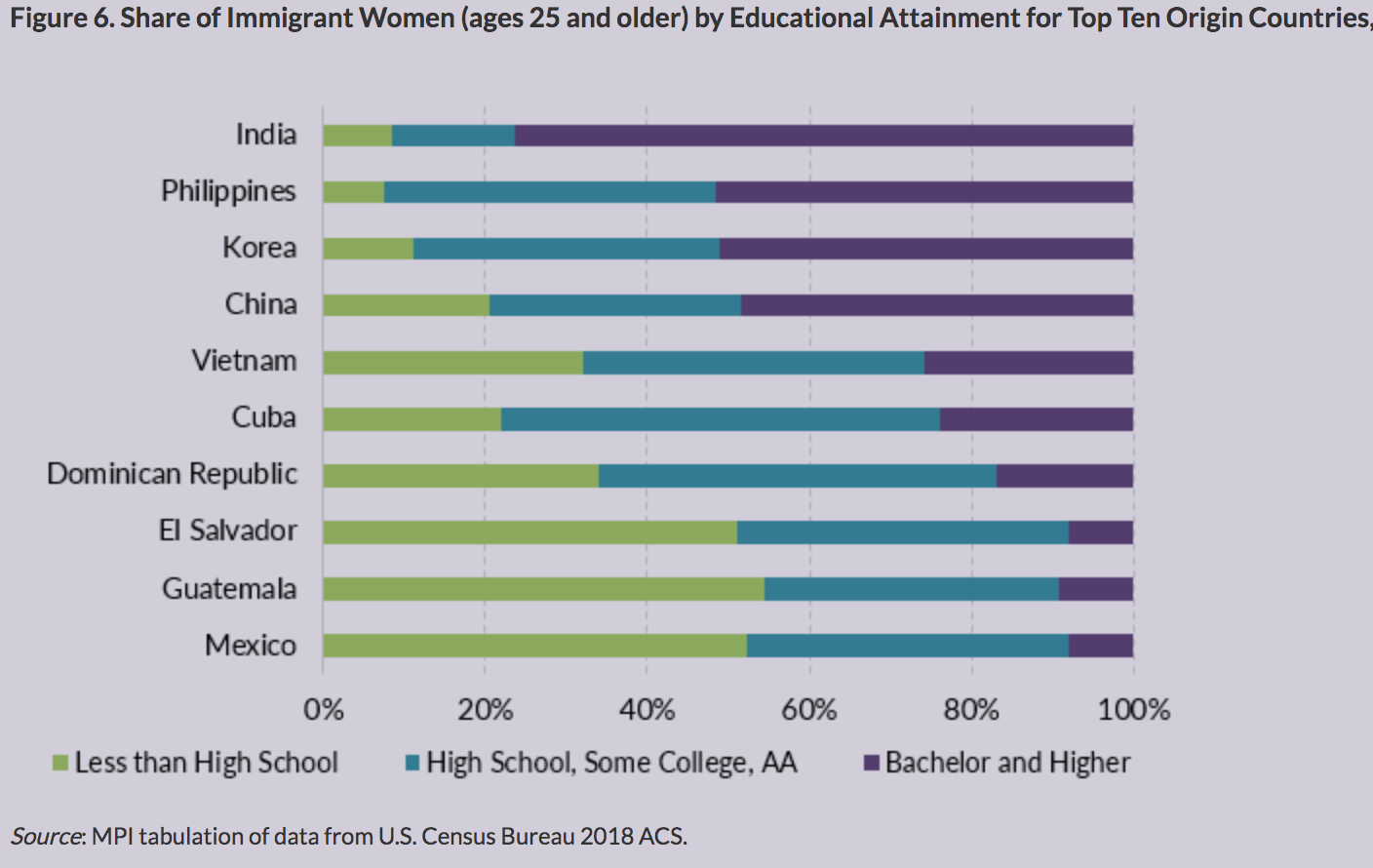

However, educational attainment varied substantially by country of origin. Among the ten largest origin groups (each with at least 1 million immigrants in the United States)—Mexico, India, China/Hong Kong, the Philippines, El Salvador, Vietnam, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Korea, and Guatemala—women from Asian countries were more educated than those from Latin America (see Figure 6). Cuban immigrants were the exception as they were the most likely to have earned a high school or an associate’s degree, although less likely than Asian female immigrants to have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Though still lower in educational attainment than their male counterparts, women from India (76 percent), the Philippines (52 percent), and Korea (51 percent) were more likely to be college graduates among the top ten countries; women from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico (7-8 percent) were the least likely.

Limited English Proficiency. Forty-eight percent of all female immigrants above the age of 5 in the United States were Limited English Proficient (LEP), according to the 2018 ACS. The share who were LEP varied by country of origin, reflecting to a large degree the prominence of English in home countries. For example, 83 percent of Bhutanese, and 71 percent of Honduran and Salvadoran female immigrants, 70 percent of Burmese, 69 percent of Guatemalans, and 68 percent of Vietnamese were LEP, compared to only 14 percent of Nigerian and 4 percent of Canadian female immigrants.

In many cases, there was no significant variation in LEP share between immigrant men and women from the same country. Several countries stood out: Men from Sudan, Congo, Uganda, Somalia, Afghanistan, and Iran were less likely to be LEP than women; the opposite was true for immigrants from Gambia, Lithuania, Singapore, and Serbia.

Note: The term “Limited English Proficient” refers to persons ages 5 and older who reported speaking English “not at all,” “not well,” or “well” on their survey questionnaire. Individuals who reported speaking only English or speaking English “very well” are considered proficient in English.

Employment and Occupations. Although immigrants (ages 16 and older) as a whole participated in the civilian labor force at higher rates than native-born individuals (66 percent versus 62 percent), immigrant women had a slightly lower rate of workforce participation than their native-born counterparts (57 percent versus 59 percent).

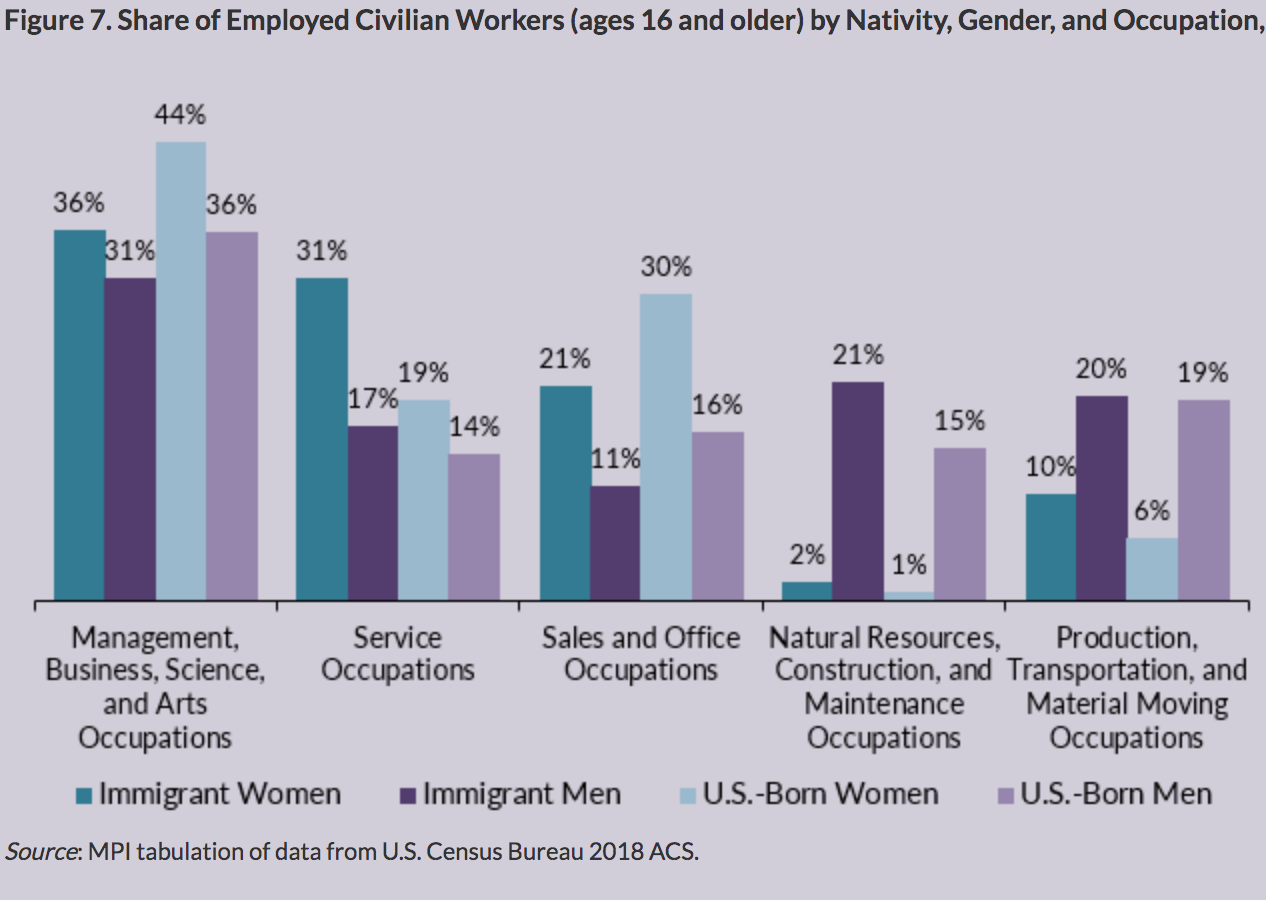

As of 2018, there were more than 11.9 million workers who were immigrant women (ages 16 and older), comprising 16 percent of all female workers and 8 percent of all U.S. civilian workers. Thirty-six percent of immigrant women were employed in management, business, science, and arts occupations (which includes education and higher skilled health-care occupations); followed by 31 percent employed in service occupations (such as hospitality); (see Figure 7). Immigrant women were as likely as U.S.-born men to be employed in management, business, science, and related occupations but much less likely than U.S.-born women. At the same time, immigrant women were much more likely to be employed in service occupations than the other groups.

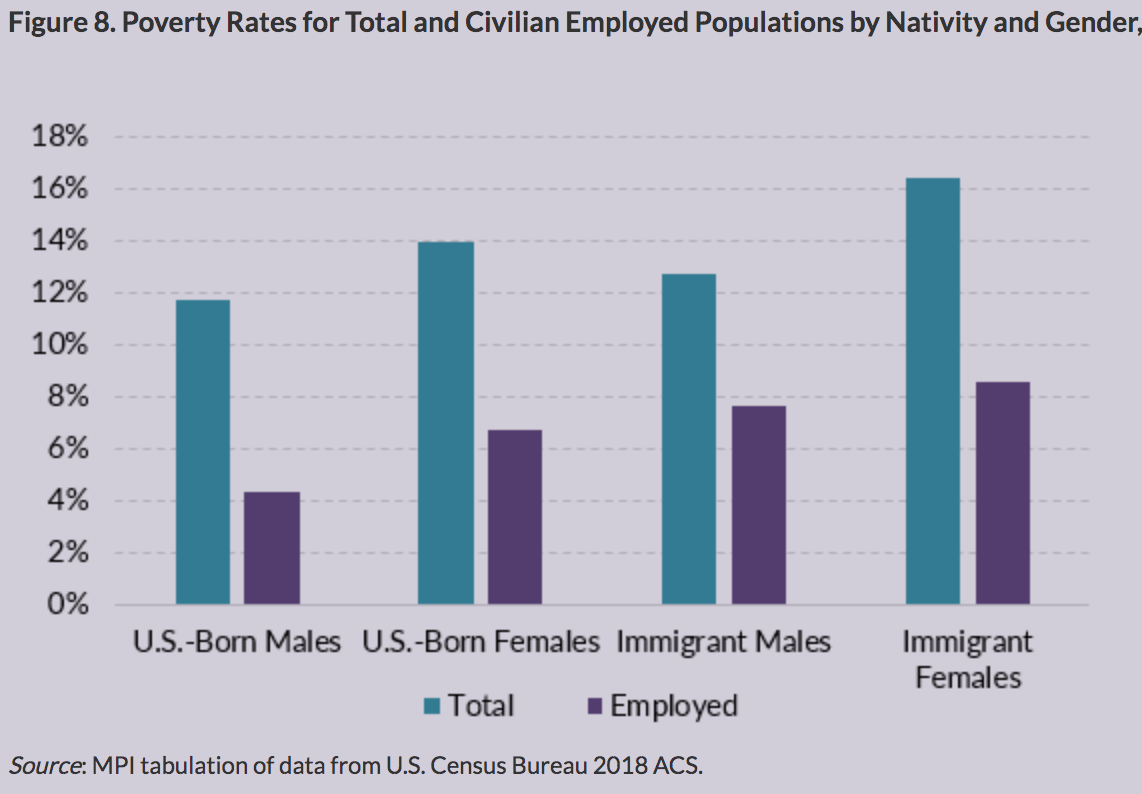

Poverty. Immigrant women fared worse on poverty measures than either immigrant men (with 16 percent living in poverty compared to 13 percent for their male counterparts) or the native-born population (with 14 percent of U.S.-born women and 12 percent of U.S.-born men in poverty). However, employed female immigrants (9 percent) were less likely to be in poverty than immigrant women overall (16 percent); they were roughly as likely as their male counterparts to be working poor (8 percent) (see Figure 8).

Note: Whether an individual or household falls below 100 percent of the federal poverty level depends not only on total family income, but also on the size of the family, the number of people in the family who are children, and the age of the householder (under/over age 65). A single individual is considered to be a family of one. A household is the total number of families living in the same residence.

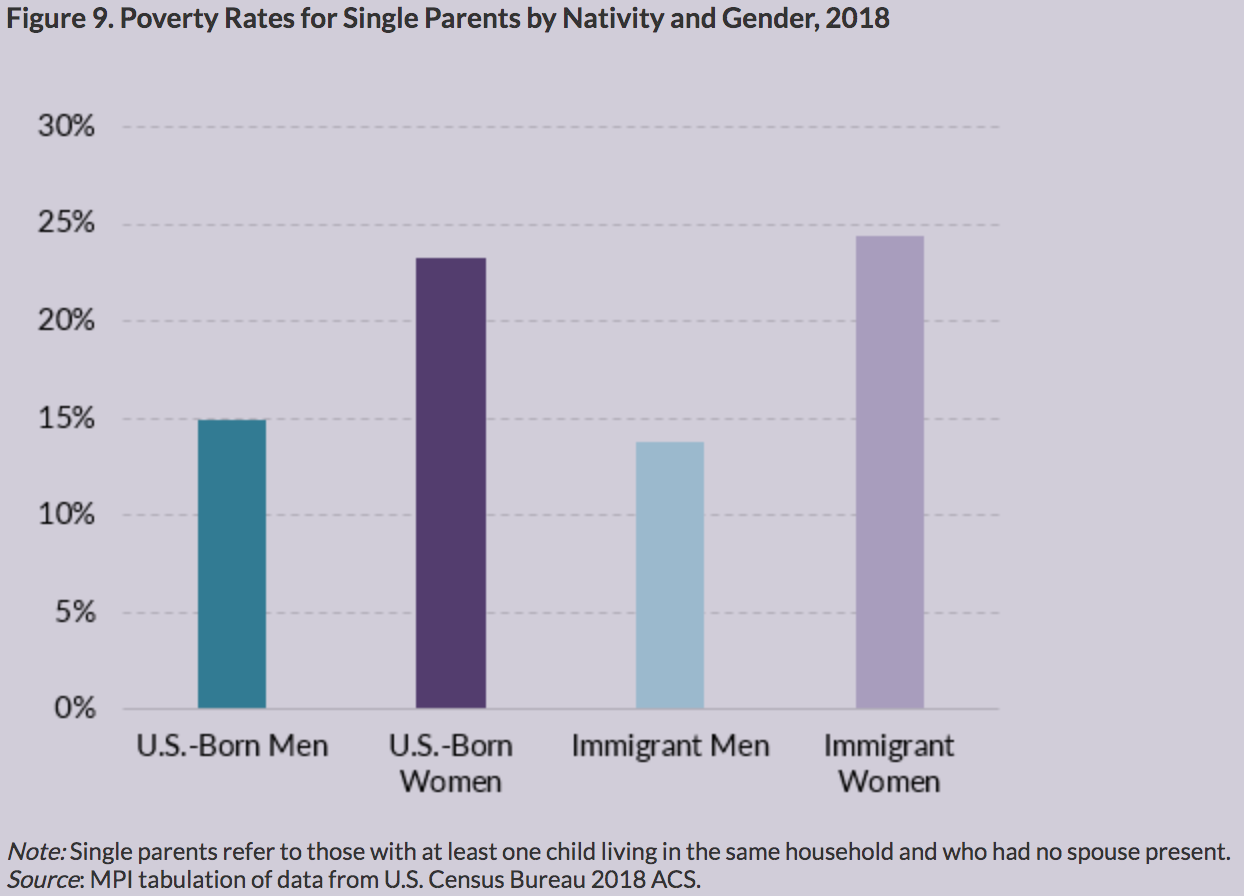

Single parenthood has been a predictor for poverty; single mothers, in particular, encounter significant financial hardship. As of 2018, almost one-quarter of single mothers, regardless of nativity, lived in poverty, compared to 14-15 percent of single fathers (see Figure 9).

Health Insurance. The passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2014 expanded access to health insurance in the United States. Nonetheless immigrants are nearly three times as likely to lack health insurance than their U.S.-born counterparts (20 percent versus 7 percent).

In terms of gender difference, immigrant women were less likely to be uninsured than immigrant men (17 percent versus 22 percent), and more likely to be covered by public health insurance (33 percent versus 27 percent), partly due to public health insurance programs available to low-income mothers. Compared to native women, immigrant women were much more likely to be uninsured (17 percent versus 6 percent) and somewhat less likely to be enrolled in either public or private insurance programs (see Figure 10).

Citizenship and Immigration Status. As of 2018, 53 percent (12.3 million) of all immigrant women were naturalized U.S. citizens, compared to 48 percent of immigrant men (10.4 million). Women accounted for a larger share among new naturalized citizens in 2018 (55 percent of 762,000 new citizens) and among legal permanent residents (53 percent of 1.1 million new green-card holders) than men, according to data from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Among refugees admitted and those granted affirmative asylum in 2018, women and men represented equal shares.

In contrast, the female share of migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border is much lower; it was 35 percent in 2019. Still, that share is up from earlier years (e.g., 14 percent in 2012), in part because more families are migrating.

Another category of migrants—spouses of highly skilled temporary workers—also bucks the trend: Of the 6,800 employment authorization cards approved for certain spouses on H-4 visas, 92 percent went to women.

Unauthorized Population. Women composed 47 percent of the 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States in the 2012-16 period, according to the latest estimates from the Migration Policy Institute. In Hawaii and Missouri, the female share was higher: 56 percent in Hawaii and 50 percent in Missouri. On the other end of the continuum, the share of females among the unauthorized was lower than the national share by 5 or more percentage points in South Carolina and Louisiana (42 percent each) and Mississippi (38 percent).

Visit the Data Hub’s Unauthorized Immigrant Population Profiles for in-depth profiles of this population’s characteristics nationally and in 41 states, the District of Columbia, and the 135 counties with the largest unauthorized populations.

Originally published by the Migration Policy Institute’s online journal, the Migration Information Source, as: Jeanne Batalova, “Immigrant Women and Girls in the United States,” Migration Information Source, March 4, 2020, https://www.migrationpolicy.