Emma Lazarus’s Petrarchan sonnet is an awkward vehicle for defenses of American greatness—perhaps because so many of those who quote it miss its true meaning.

The words of Emma Lazarus’s famous 1883 sonnet “The New Colossus” have seemed more visible since Donald Trump’s election. They can be found on the news and on posters, in tweets and in the streets. Lines 10 and 11 of the poem are quoted with the most frequency—“Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”—and often by those aiming to highlight a contrast between Lazarus’s humanitarian vision of the nation and the president’s racist rhetoric.

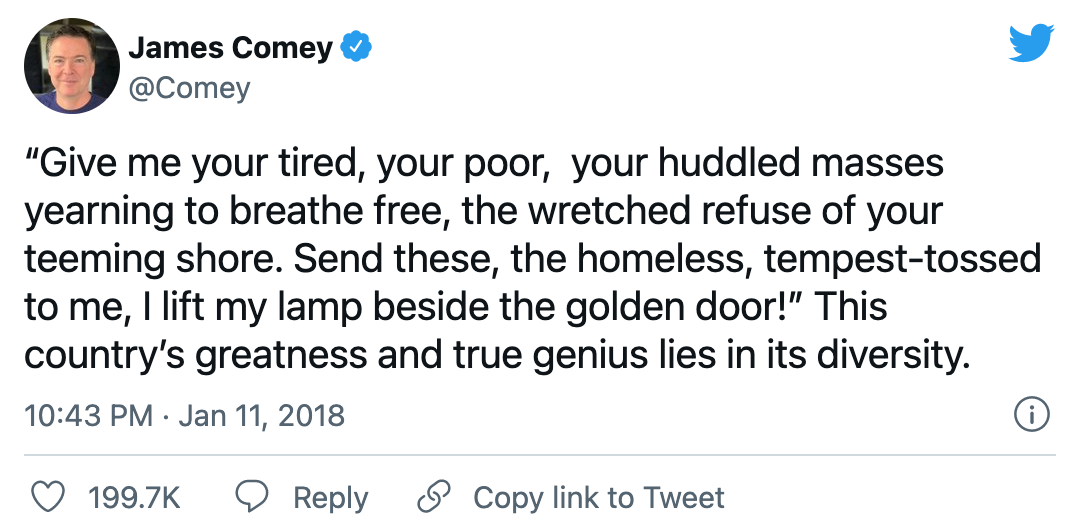

After reports that Trump had described Haiti, El Salvador, and African nations as “shithole countries,” the former FBI director James Comey tweeted a bit of the sonnet, along with his interpretation of its meaning:

Several other public citations of Lazarus assume that her poem is reducible to a message about the value of diversity. Comey’s tweet echoes Nancy Pelosi’s interpretation from early 2017: “You know the rest. It’s a statement of values of our country. It’s a recognition that the strength of our country is in its diversity, that the revitalization … of America comes from our immigrant population.” For Comey, diversity is greatness. For Pelosi, diversity is both the existing strength of America and its source of revitalization. To marshal Lazarus’s poem in support of a redefinition of American greatness, however, is to capitulate to the terms of Trump’s exceptionalism—and to ignore the poem’s own radical imagination of hospitality.

A little like Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” published in 1916, “The New Colossus” is one of those poems that is constantly rediscovered and recontextualized. Whether the popularity of “The New Colossus” is a consequence of the poem’s timelessness, its curious forgettability, or its “schmaltzy” sincerity, writers, readers, and politicians resurrect Lazarus’s sonnet to speak directly to a present moment in which anti-black racism, xenophobia, immigration bans, and refugee crises define the terms of U.S. and European political discourse.

The story of the poem’s creation has circulated almost as widely as the lines of Lazarus’s poem. The Jewish Lazarus was a prolific writer in multiple genres, a political activist, a translator, and an associate of late-19th-century literati—including Ralph Waldo Emerson and James Russell Lowell. She wrote the sonnet, after some persuasion by friends, for an auction to raise money for the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. But the details of the poem’s production and of its author’s biography do not fully capture the conditions under which the poem emerged, conditions that help to explain the poem’s message to its immiserated masses.

“The New Colossus” emerges at a pivotal moment in history. The year before Lazarus’s poem was read at the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund Art Loan Exhibition in New York, in 1883, the Chinese Exclusion Act became the first federal law that limited immigration from a particular group. Though set to last for 10 years, various extensions and additions made the law permanent until 1943. The year after Lazarus’s poem was read, the European countries met in Berlin to divide up the African continent into colonies. “The New Colossus” stands at the intersection of U.S. immigration policy and European colonialism, well before the physical Statue of Liberty was dedicated. The liberal sentiments of Lazarus’s sonnet cannot be separated from these developments in geopolitics and capitalism.

The poem’s peculiar power comes not only from its themes of hospitality but also from the Italian sonnet form that contains them. A Petrarchan sonnet is an awkward vehicle for defenses of American greatness. Historically, the epic poem has been the type of poetry best suited to nationalist projects, because its narrative establishes a “storied pomp” in literature that has yet to exist in the world. The sonnet, in contrast, is a flexible, traveling form, one that moved from Italy to England. It is more at home in the conversations, translations, and negotiations between national literatures than in the creation or renewal of national eminence.

U.S. poets across the 20th century, from Claude McKay to Gwendolyn Brooks to Jack Agüeros, have turned to the sonnet for a critique of American greatness rather than a liberal redefinition of it. These poets, in sonnets such as McKay’s “The White City,” Brooks’s “A Lovely Love,” and Agüeros’s Sonnets From the Puerto Rican, expose that greatness as being predicated on the slavery, denigration, and exploitation of colonial, African American, and Latinx subjects. This difficult, “high literary” form, ostensibly the property of a white European elite, has become one of the available tools to take apart the racism of society and the ravages of a global economy. To place Lazarus in that lineage is to see her poem as something more than a competing vision of American greatness, as Comey and others would have it.

In the afterlife of Lazarus’s poems, the words that the statue cries out in the sestet—the final six lines of the poem—have often been treated as though they were identical to the voice speaking the rest of the poem. They are, however, the imagined voice of a figure within the poem. Over the 14 lines of the sonnet, the poem moves from making a negative comparison to the Colossus of Rhodes to animating the “new Colossus” with a voice, an instance of what literary critics call personification or, to use the more unwieldy term, prosopopoeia:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

What the poem does, through its shifts in figurative language from comparison to personification, is just as important as what it says explicitly. Rather than standing guard, or extending open arms, the “Mother of Exiles”—a gendered, racialized figure—cries out with its “silent lips.” The difference, then, is not only in what this Colossus represents—its liberal values of hospitality, diversity, and inclusion—but also in the speaking figure that the poem creates. The sonnet ends by compelling its readers to hear this invitation. It is a response that anticipates the cries of affliction that it knows are coming.

The philosopher Simone Weil argues that the impersonal cry of “Why am I being hurt?” accompanies claims to human rights. To refuse to hear this cry of affliction, Weil continues, is the gravest injustice one might do to another. The voice of the statue in Lazarus’s poem can almost be heard as an uncanny reply, avant la lettre, to one of the slogans chanted by immigrants and refugees around the world today: “We are here because you were there.” The statue’s cry is a response to one version of Weil’s “Why am I being hurt” that specifies the global relation between the arrival of immigrants and the expansion of the colonial system.

The cry of the tired, poor, and huddled heard by Lazarus’s poem is manifest today within the poetry written and recited by women exiles, freedom fighters, imprisoned activists, and detainees. “A Female Cry,” by the Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour, asserts the right, not to resources, but to something more than an accommodation by the existing system. Here are the final two stanzas of the poem:

O my dream, kidnapped from my younger years

Silence has ravaged us

Our tears have become a sea

Our patience has bored of us

Together, we rise up for sure

Whatever it was we wanted to be.

So let’s go

Raise up a cry

In the face of those shadowy ghosts.

For how long, O fire within,

Will you scorch my breast with tears?

And how long, O scream,

Will you remain in the hearts of women!

Tatour demands more than patience and tears, of which she has more than enough; she calls for an uprising on behalf of “whatever it was we wanted to be.” Tatour’s addresses—to dream, fire, and scream—are the addresses of the genuinely tired, poor, and huddled (as well as detained and imprisoned) rather than those of the model liberal subject. The colossal cry has burst its sonnet’s narrow cell: It appears as one possible form in which the poetry of a global uprising anticipates and prefigures the moment of revolution itself.

Pelosi and Comey, however distinct they are as political figures, quote Lazarus to support a liberal narrative of American exceptionalism, based on multiculturalism, diversity, and inclusion. Yet the collective, immiserated masses invited and welcomed by these lines are tired, poor, and huddled—and at odds with the empowered, individualized “hard worker” that Comey and others reproduce as the ideal image of the immigrant.

It is not that people shouldn’t be acknowledged for their hard work, of course; it’s just that that shouldn’t be the most relevant criterion for the performance of political and economic justice. The language of diversity and inclusion has become one of the prominent means by which the nation currently manages its political and economic crises by seizing the power of moving bodies as human capital. If the justification for managing borders relies entirely on the recitation of liberal values—however necessary it may be to continue to affirm them in the midst of their relentless negation—there is no guarantee that “liberty” will be fully realized.

Lazarus’s poem begins by repudiating the greatness to which Comey summons the poem as witness. It continues with a denial of nationalist narratives that are based on historical claims of ancient possession: “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!”

What might be more important than the values that the New Colossus speaks—ethical claims to rights, liberty, and hospitality that, despite their reiteration, have hardly succeeded in preventing the worst violence of the late 19th and 20th centuries—is the silence that the poem refuses. And to hear this silence is to read the poem’s sonnet as voicing a cry that those who passionately recite its words, from Pelosi to Comey, as well as those who violently deny them, might well train themselves to hear.

This article was reprinted with permission by Walt Hunter, an associate world-literature professor at Clemson University and author of Forms of a World: Contemporary Poetry and the Making of Globalization. This article was published in The Atlantic on January 16, 2018.